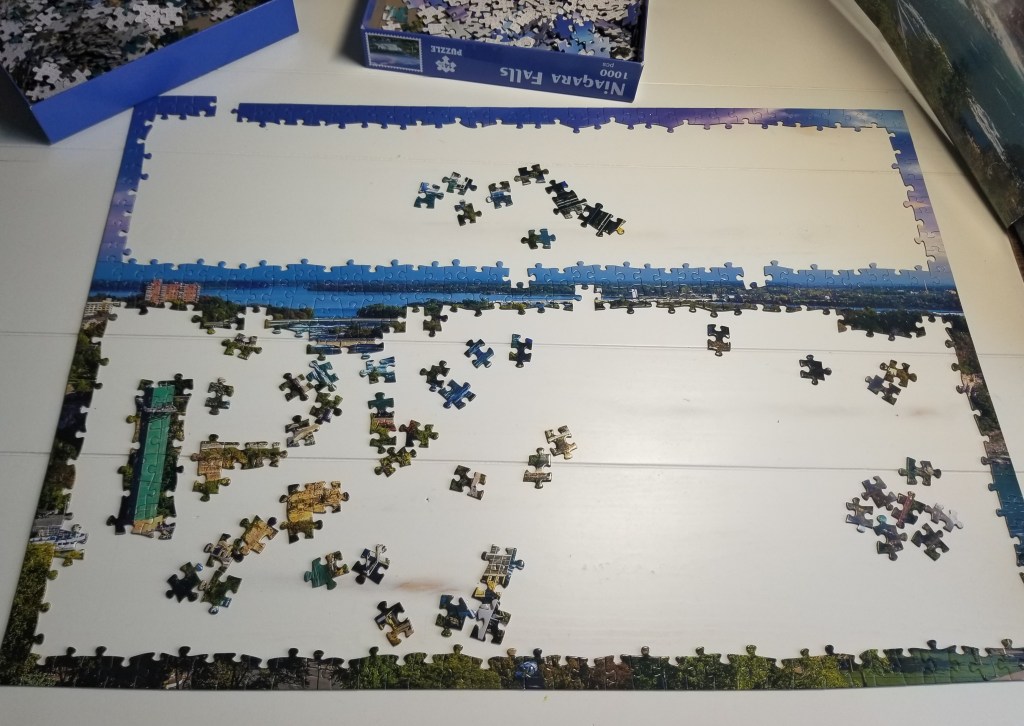

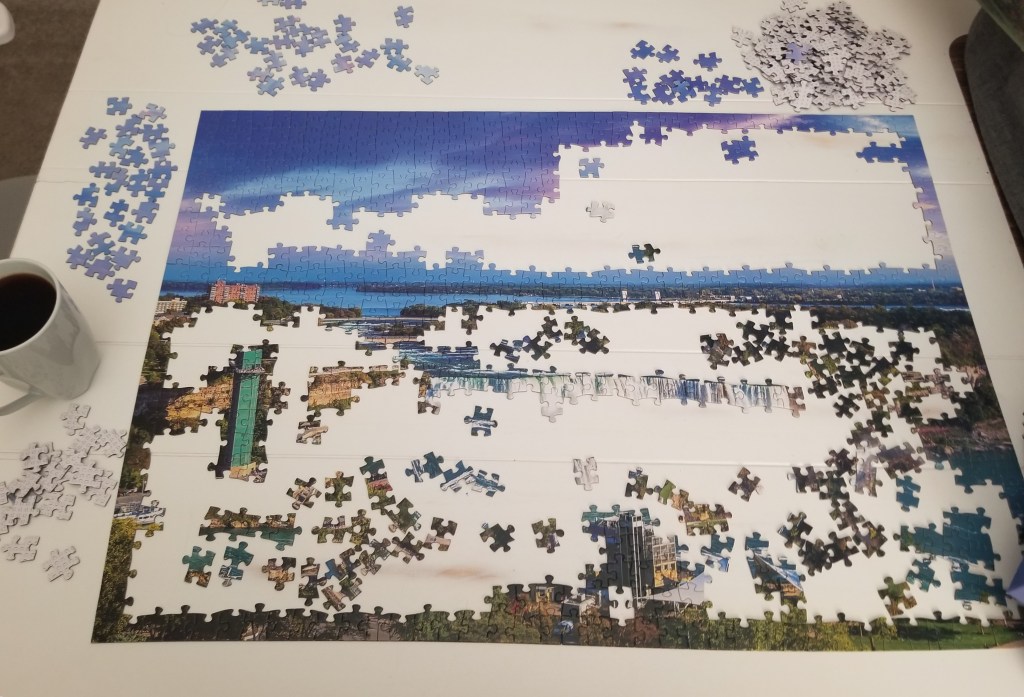

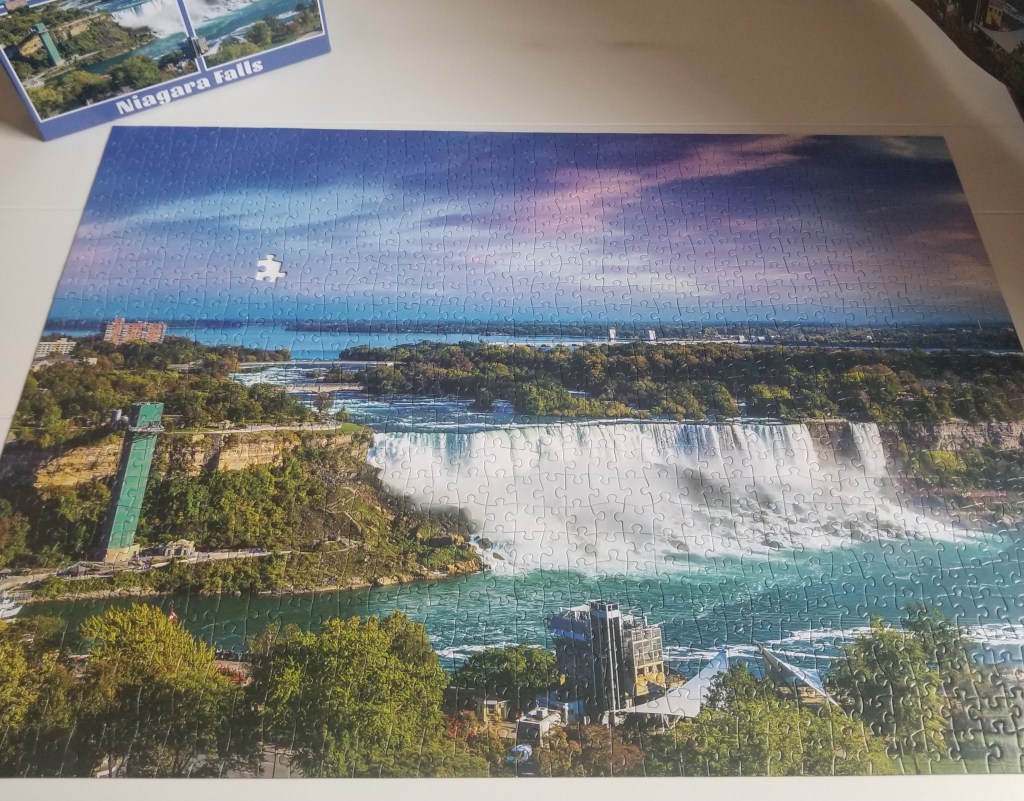

A week has passed since my National Puzzle Day post in which I recounted how my dad and I put together jigsaws side-by-side when I was growing up. The memory inspired me to buy a 1,000-piece puzzle in his honor. I quickly remembered how much I loved puzzling then and completing it became a bit of an obsession. I finished the next day and promptly bought a four-pack of 1,000-piece jigsaws. I finished one of those in two days as well.

Working on those two puzzles gave me a lot of time to ruminate, and I found myself finding extraordinary–and yet, simple–lessons from those boxes of pressed cardboard. Remember the 1988 book All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten: Uncommon Thoughts on Common Things by Robert Fulghum? Well, this post is a take-off on that. Jigsaw puzzling has taught me…

1. How to work together

In puzzling, getting the edge pieces–the boundaries–sorted out and placed is a job multiple puzzlers can tackle together and not get in each other’s way. With that in place, it then helps for individuals to pick an area of the puzzle they’re attracted to and concentrate on reconstructing it: structures, sky, forest, mountains, water.

It’s like this in life too. A happy team (or family) has tasks it tackles together as well as individual assignments. Overall strategy is a great team task, along with dividing the strategy into action items. At that point, it makes sense to poll team members for their preferences and have each one take ownership in completing a part of the whole.

Helping each other along the way is good, too. In puzzling, that meant if I found a piece dad needed, or vice-versa, we passed it along. Most of us humans appreciate knowing someone is on our team and looking out for us, too. Sometimes it’s a phone call, text, lunch or small gift that lets others know they’re in our thoughts and we care about them.

2. Working alone also has advantages

Puzzling solo helps me clear my mind so new ideas can surface. It means I can implement my own strategy from start to finish, but it also mean I can learn to improve my strategy over time. We should never be afraid to learn a new way of doing the same old thing. We can, in fact, teach ourselves. That’s what learning is, right?

One thought that occurred to me while resurrecting my puzzle love was how sorting out pieces resembled the myth of Eros and Psyche. One of Psyche’s tasks given to her by the goddess Aphrodite as punishment was to sort a huge pile of seeds overnight, according to kind. In Psyche’s case, ants helped her. Just think of those “ants” as little workers in our brain–synapses that replicate–showing us how to surmount most any obstacle.

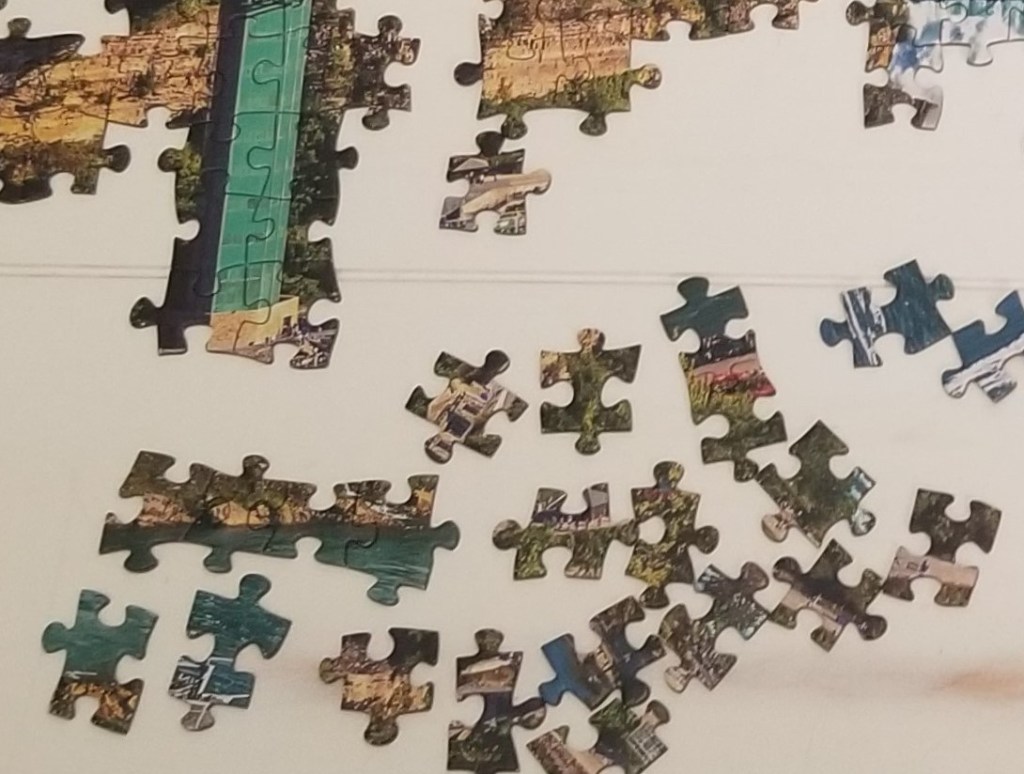

Working alone on any project may seem like Psyche’s chore. It may seem an overwhelming task at first, but it forces us to look at each individual element and its characteristics and assign it to its pile. In puzzling, the sort may be according to piece shape, piece color, or the section markings on the back. Whichever category of sort we choose, we come to know the elements we handle intimately.

And there’s no limit to what someone can accomplish when she sets her mind to it.

3. Names are important

Did you know puzzle-piece parts have names? The rounded protrusions are called interjambs, as well as knobs, bumps, loops, outies, keys and male. Hollowed-out spaces are most commonly known as blanks, but are also called pockets, sockets, slots, innies, locks and female. I like it that puzzle-piece parts have names and that those names have synonyms. It tickles my love of language.

Exploring the “unconscious” side of objects and words makes for a deeper experience of life, just as being present with others in whatever moments we spend together makes for more honest and empathetic relationships. That sort of authenticity begins with a knowledge of words and their insides because they can lead us to a knowledge of the insides of other people.

4. Read the directions

I can’t begin to count the number of hours my dad wasted by throwing away directions. Whether it was how to operate the lawnmower or hang a picture, he wanted to figure it out on his own, I guess. A laudable goal, I suppose, but why reinvent the wheel?

Jigsaw puzzles don’t come with “directions” per se. But they do come with some guides these days that dad and I didn’t have. On the backs of the pieces are letters indicating which sector the piece goes into. If you have a lot of green area, for instance, it helps to sort the pieces according to location in the puzzle. If you think that’s cheating (my dad would), consider that it divides the larger puzzle into four or six smaller ones and helps you focus your efforts.

Puzzles these days also come with fold-out pictures of the finished product. Dad and I always had to squint to look at the picture on the box top. And we couldn’t use it for reference and for sorting pieces at the same time.

Tapping into all the aids available helps with ALL life tasks. Do your research. Build on the successes of those who have gone before. Understand the big picture before getting started. What is success supposed to look like? When we’re finished, what will we want to say we accomplished? It’s easier to reach a goal that’s been identified at the start.

That said…

5. There’s often no one right way

One vivid memory of working puzzles with my dad is that he seldom laid in a piece that didn’t fit. He studied the shapes, sizes and color variations like a detective and didn’t place his piece until he was sure it was the right one.

Then, I thought he was over-cautious. I would expend a lot of time and effort trying each piece everywhere it might fit. Sometimes I would even sort the pieces into like shapes first, then try them everywhere. Looks can be deceiving, I thought. I never wanted to miss a match for lack of trying. There’s something to that approach.

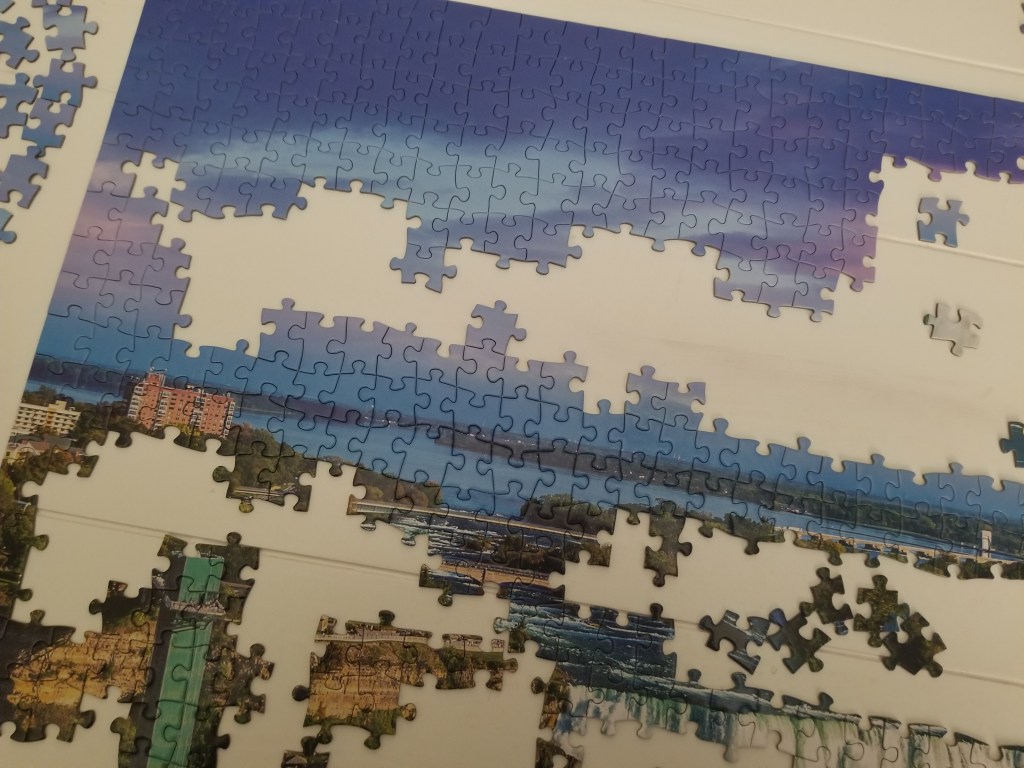

Dad never criticized me, but he kept on doing it his way. Now that I’m older, I find I like his way better, with puzzles anyway (doesn’t work so well with home repairs and such). It’s quieter and teaches me to be more observant, both of the picture I’m recreating as well as what thoughts are floating around in my head. I organize them as I organize the puzzle.

In last week’s post I recommended strategies for attacking puzzles, such as starting with the edges; focusing on a line where change is apparent, such as a horizon line or a shift from land to water; concentrating on a particular area, such as the sky; or committing to completing a structure.

The truth is, all those ways work equally well. There are likely some strategies I’ve missed. The point is to go with the flow with puzzles and with life. Do what interests you. Follow what feels right.

6. Nothing is perfect, EVER

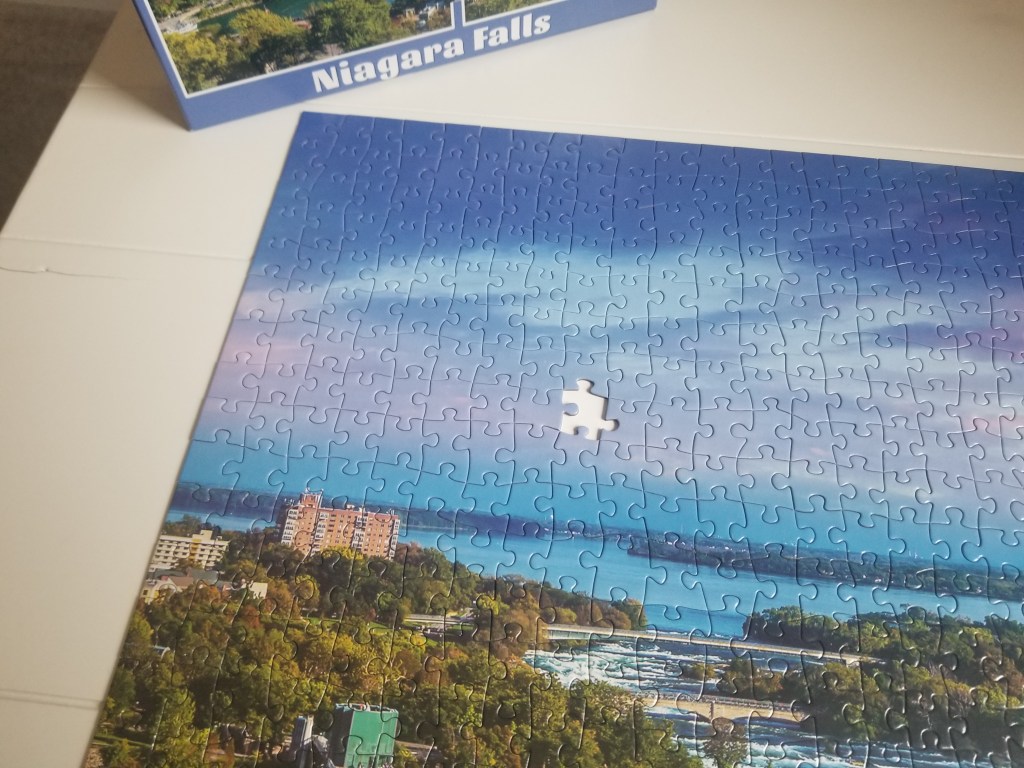

Both puzzles I’ve put together in the last week have been missing one piece. I used to find it annoying when this happened. But this time around, I just sat with the idea and contemplated the negative space.

There wasn’t much to do about it. I could get a refund on the puzzle or a replacement puzzle. The refund would allow me to buy another puzzle. A replacement was kind of silly, as I wasn’t going to put together the same jigsaw twice just to pop in that last piece in the middle of a sky or forest or desert. The joy was in the doing, not the finishing. A scene in nature is never finished anyway. It’s always evolving.

Life is like that. We build things, plan, do, but it never comes out perfect, and a year later it’s irrelevant. As I age, I’m learning to let go of my perfectionism, my unrealistic expectations. It reminds me of the opening lines of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

I say, those happy families are all distinct from one another, too, and far from perfect and maybe not all that happy below the surface. My point being that imperfection is what distinguishes people, places, animals, situations–and makes them interesting. A different kind of beauty emerges from the imperfect, not what’s perfect.

It’s like the Japanese art of kintsugi where broken pottery is mended with gold. Legend has it that a 15th-century military ruler, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, sent a broken tea bowl back to China to be repaired. He was disappointed with the result and asked a local craftsman to find a more aesthetically pleasing method of repair. The solution was to emphasize the cracks in the bowl with precious metals rather than conceal them.

We are all broken tea bowls, puzzle pieces stamped into cardboard. Pieces, chips get lost along the way from molding to packaging to wear and tear. No one and no thing makes it out of life whole. Celebrate what’s lost along the way as well as what’s gained.

7. Enjoy the journey

Celebrate the process of putting together a jigsaw, solving some other kind of puzzle, or undertaking any task. When I was planning my wedding I really wasn’t all that interested in GETTING married, but I was interested in BEING married to Chris, the man who has been my husband for more the 35 years.

Each day is a new adventure with him as well as with any task I undertake. Every time I open a new puzzle box, I feel a little twinge of excitement, and that twinge is really what everything is about.

I’m reminded of a favorite poem by Emily Dickinson:

Exultation is the going

Of an inland soul to sea,

Past the houses — past the headlands —

Into deep Eternity —Bred as we, among the mountains,

Can the sailor understand

The divine intoxication

Of the first league out from land?

Use the comments to share what activity has taught you “all you really need to know”…

You might also enjoy…

- This National Puzzle Day, Unlock Your Brainpower & Your Memories

- Lessons of Brokenness in Nature: A Goose’s Tale

- Quiz Yourself: How Factfulness Changes Our Views of the World

- A Meaningful Encounter: Connecting Over Culture & History at Clinic Check-in

- The Misadventures of a Lost Stanley Drink Cup

- Exploring David Brooks’ How to Know a Person

PLEASE NOTE: This post contains affiliate links.

Leave a comment