With great sadness I learned a week ago of the death of my friend Max–Maxime Noel, a resident of Morville, Belgium–on 4 January 2025, at the age of 42. Our connection was such a serendipitous meeting of souls that I wanted to share it. Like all the best stories, this is a story of many others who connect through Max. Lest anyone question the impact a single life can have in so few years, they only have to look to his legacy, to which I will try to do justice.

First off, Max and I never physically met. The wonders of Internet search engines brought us together initially, and emails followed. Then, as my acquaintance grew to include his partner, Frederique, online translation applications helped.

First contact

Around 2014(?), a year or so after converting my dad’s World War II story into a website, I received an email from a man in Belgium looking for information for a book he was researching. His search for information on the 474th AA-AW, my dad’s unit, eventually hit on that website, “No Major Goofup.” AA-AW stands for antiaircraft artillery-automatic weapons, and dad’s battalion commandeered half-tracks (tires upfront, tank treads in back) mounted with a minesweeper, 50-caliber machine guns and a 37-caliber canon.

This man, Maxime Noel, was looking for information on the 474th’s first casualty. He planned to write a book on the temporary World War II military cemetery at Fosses-la-Ville, Belgium, near his home, and this fallen soldier had been temporarily interred there until the war ended and his body could be returned to his family in the USA.

“Do you know anything about John P. Cairo?” he wrote. I couldn’t believe the words on the page! My website included a sizable passage on John, that first casualty of the 474th, who had been a good friend of my dad’s. Dad passed away in fall 2013, and how I wished I could have shared this story with him. I’ll tell the part about John in dad’s words, as recorded on that website.

Dad & John Cairo

“John and I were good friends,” dad said. “When he was on our gun crew, he and I usually dug our foxhole together. We would have lots of friendly discussions and only a few loud ones. He was raised near Altoona, PA. [Dad came from New Kensington, PA.] John and I discussed prior to the [D-Day] invasion about whether we would go home again or not. I always felt I would, but John didn’t think he’d make it.”

Near Theux, Belgium, John Cairo was shot in the stomach in a gun accident and died soon after. “John had just eaten breakfast and was going out to check on how the other guys in his crew were doing,” dad said. “They were adjusting the headspace in a 50-caliber gun on one of the half-tracks and had the gun barrel depressed, which it shouldn’t have been, because if you get it too tight, it will fire automatically, and that’s what happened. When it fired, it blew John’s stomach and its contents out his back.”

John reportedly was conscious as they loaded him into an ambulance, and he told his pals he’d be back with them soon. But he didn’t make it and was eventually buried in the temporary cemetery at Fosses-la-Ville, 60 to 70 miles west of Theux.

“About nine or 10 years after I got home, I went to look up John’s family,” dad said. “His only remaining relative was a stepsister. Needless to say, she was very happy I came to visit her, and we both cried. No one else from the unit had ever written to or visited the family. But she knew how John had been killed through a friend who had worked in the Pentagon. I promised to send her some pictures of John and me, taken in the states, and I did,” which explained why there were no pictures of John in dad’s extensive war-time photo collection.

After reading this, Max sent me this photo of John, which he had located through Army records, and I added it to my dad’s website. This sharing of information kicked off our long-distance friendship.

Temporary cemeteries & Fosses-la-Ville

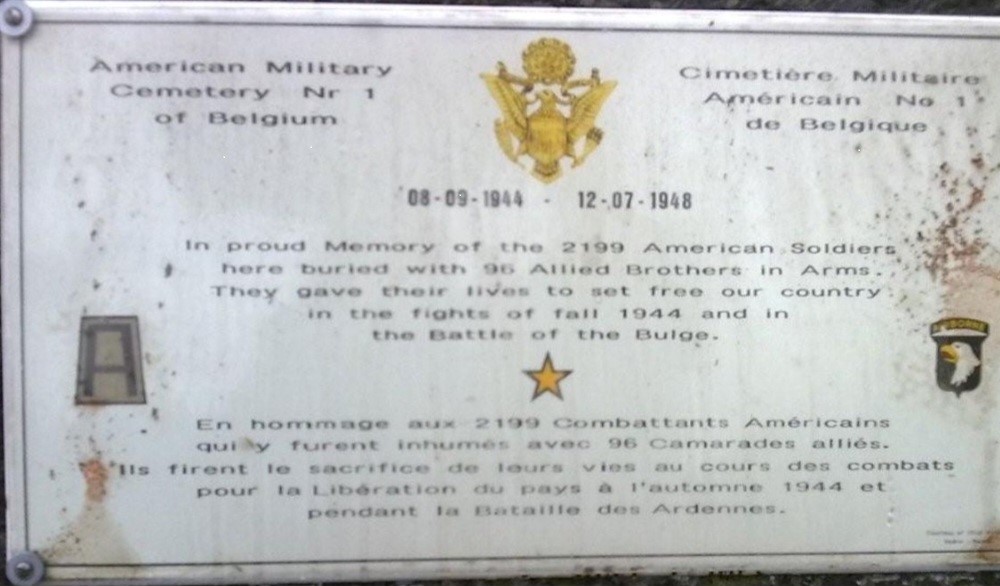

I never realized until my exchanges with Max that many, many soldiers were buried in temporary cemeteries and their remains relocated to official military cemeteries in Europe or repatriated stateside after the war ended. Fosses-la-Ville was the first of those temporary cemeteries in Belgium, opened by the 1st Army 8 September 1944. John Cairo died 12 September, which would have made him one of its first inhabitants.

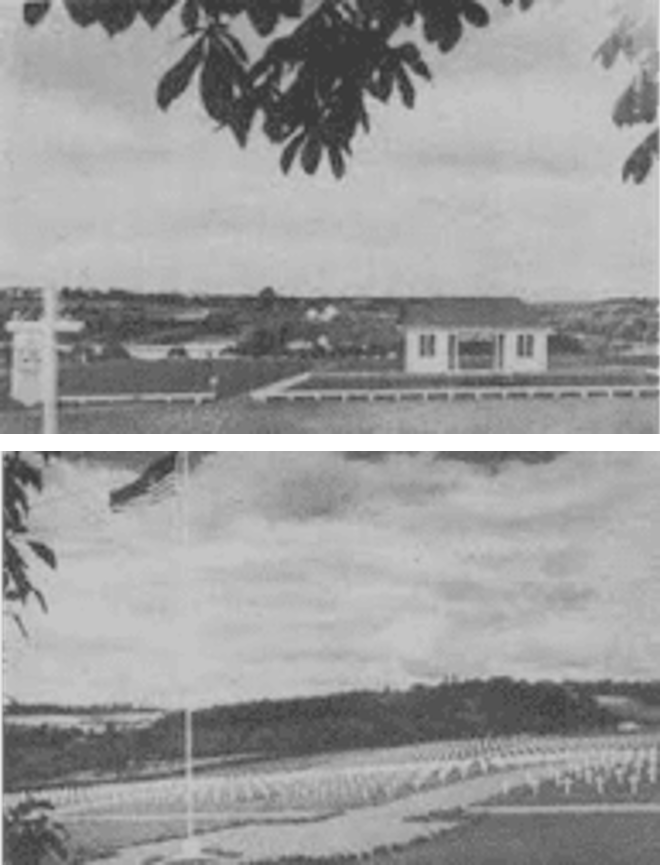

The small town of Fosses-la-Ville is located on the highway to Charleroi, Belgium, 11 miles southwest of Namur, Belgium, and 190 miles northeast of Paris, France. The road was one well-traveled by American troops in 1944 and 1945. The cemetery sat on a picturesque hill called Campagne du Chene, with the La Biesme riverbed and Bois de Sainte-Brigide d’Irlande (forest) to the north, and the Collegial church to the east.

Burials continued there until February 1945, and the cemetery eventually held 2,199 United States soldiers and 96 men from other Allied nations’ armies. The remains of an additional 1,600 German soldiers were buried on a lower level separated by a large lawn. Most of those laid to rest at Fosses were casualties of the liberation of Belgium and Netherlands, the entry of the first American troops into Germany, the German counter-offensive in the Ardennes in December 1944, and victims of air crashes.

Cemetery grounds then consisted of a pavillion guarded by seven U.S. Army soldiers, shown in the above right photo (top) and surrounded by a forest of small crosses arranged in 11 square plots with 200 graves each, shown above right (bottom). Max located these photos and shared them with me.

The cemetery was definitively decommissioned 12 July 1948. All that remains now is the plaque pictured below, set, suitably, in front of what is now a playground and park.

Diligent research produces results

Max and I continued to exchange photos and stories, and he kept me updated about his research, as well as his growing family, job changes, and remodeling a farmhouse in the Belgium countryside around Morville. In March 2016, after hearing of the terrorist attack on the Brussels airport, I emailed to check on him and found he’d been at the airport that day working as an electrician. He was unharmed, but greatly shook up by the death, destruction and confusion.

Last I’d heard in fall 2019, Max had obtained information on all but 96 of the 2,199 American soldiers who temporarily rested in Fosses-la-Ville. His research was complicated by the fact that many military records were lost in a fire at the military’s St. Louis, MO, archives in the 1970s. Many other records had to be requested through the Freedom of Information Act, which required waiting time and some expense.

But he persevered, and many interesting stories came out of his research. For one, he was able to direct a woman to the Texas reburial site of her grandfather, originally buried at Fosses, even though family narrative said his body was never brought back from Europe. In another, Max tied a soldier buried at Fosses to an Arkansas high school class ring found onsite and displayed in the small museum of a local collector. Max located the man’s daughter, who was an infant when he died and had never met him, and eventually the ring was returned to her.

That story made the local TV news in Birmingham, AL:

Growing the online record

Eventually, with Max’s help, I compiled this information into a special page of my dad’s wartime website called, “The Belgium Connection.”

Max and I hadn’t emailed of late, but I kept in touch with his partner, Frederique, via Facebook, where I enjoyed seeing photos of the couple’s daughters when they were born and as they grew. It was Frederique who messaged me just four days after his passing, saying she knew he would want her to let me know. I am so glad she did.

“It happened in the evening,” she noted in French. “He hadn’t been very well for a few days, and apparently he had respiratory failure, which caused his heart to stop. I doubt his research will continue. I’m going to give all his war belongings to his dad.”

I asked her for a photo of Max I could add to “The Belgium Connection” page and told her to pass along my contact information to his father, in case he decided to continue where Max left off. I so hope to hear from him.

Follow the link to view all Virtual Cemeteries by Max. If you click on individual entries you may see additional information collected, such as newspaper clippings, military records, relatives and additional photos. It’s a true treasure chest, particularly for someone searching for family relations.

Dedication, coincidence, grace, remembrance

The Internet is a vast storehouse of information, much of it false, misleading and worthless. But sifting through it you also uncover useful pieces created through the diligence of people like Max–information which can draw people together and help fill holes left by conflict, circumstance and misunderstanding.

Oddly, I’d been thinking of Max just the day before hearing of his passing. An acquaintance and I were talking about WWII and the role coincidence plays in who lives and who dies. I shared some of my dad’s experiences, how Max and I connected through them, and the fascinating stories Max uncovered.

My father often remarked on the graciousness of the Belgian people as they welcomed the American liberators. And in true form, the townspeople of Fosses-la-Ville adopted the temporary graves of these fallen soldiers, decorating them with wreaths and flowers and attending Memorial Day ceremonies up until the time the site was redeveloped.

This graciousness was also true of my friend Max, whose dedication to his task–done in what time he could carve from job and family–awes and inspires me.

It occurs to me that the meaning of his first and last names tells so much about who he was. Maxime = Maximus = greatest. Noel = Christmas. Max was a gift to so many. As you scan the faces of the Allied soldiers once buried in Fosses-la-Ville who gave their lives in the fight against the Nazis and Fascism, I hope you’ll remember Max’s face (and name) alongside them. He, too, will be missed, remembered and celebrated.

Leave a comment