Last summer, my friend Pat and I paced through the curves of our lazy-river community pool, chatting about how another pool pal, Babs (TPT#1), talks endlessly and listens little. In all fairness, Babs wears earplugs to keep the water out of her ears because she swims rather than walks, so she couldn’t possibly hear others well, even if she wanted to (which she probably doesn’t if it means she must be silent herself sometimes, LOL).

But we both like Babs anyway. Everyone does. She has a good heart, and she makes me laugh, so I added, “Well, at least she doesn’t talk about politics.”

My friend replied, “Maybe not to you…because you’re on the…other side.”

I flinched a little, and I think maybe Pat saw because she did, too, as if she realized her choice of words hit my ears with a thud.

First off, if someone asked Babs about politics, she might indeed provide answers confirming her beliefs and mine do not coincide. But I hear Babs talk to EVERYONE at the pool, and I’ve NEVER heard her talk politics. She’s all about movies and TikTok and where she got a good deal on a swimsuit. She repeats what she’s said to one until she gets all the way around the pool. So maybe Pat had her confused with someone else. (Mary of TPT#3?)

But what really unsettled me was Pat, who is a year-round friend, saw the two of us–her and I–as being on “different sides.”

We do indeed share divergent views on politics. She supports Donald Trump and I do not, but we don’t talk politics often, and we never disparage the other’s views. We mostly talk books and psychology and human behavior, where the best vintage stores and restaurants are, and what our kids are up to. We have so much in common that politics and “sides” seem small in comparison.

To me anyway.

The conversation lingered in my mind, though, and reminded me of the time my sister-in-law asked me to quit picking on her family (a cousin) on Facebook. I had merely asked her cousin why she believed as she did. I probably shouldn’t have, but I did it respectfully, and I really did want to know. I’m a curious person!!!

What set me back was that my sister-in-law of 50-plus years saw her cousin more as family than she saw me. I would take up for both my sisters-in-law before any of my cousins, but it hurt that I didn’t inspire the same loyalty. I learned my lesson not to have serious discussions on social media. You almost always find out more about people than you want to know, even ones you’ve known since you were 13.

An old story you may have heard…

A man stands by a river. A woman standing on the opposite shore shouts to him, “How do I get to the other side of the river?” He shouts back: “You are ALREADY on the other side!”

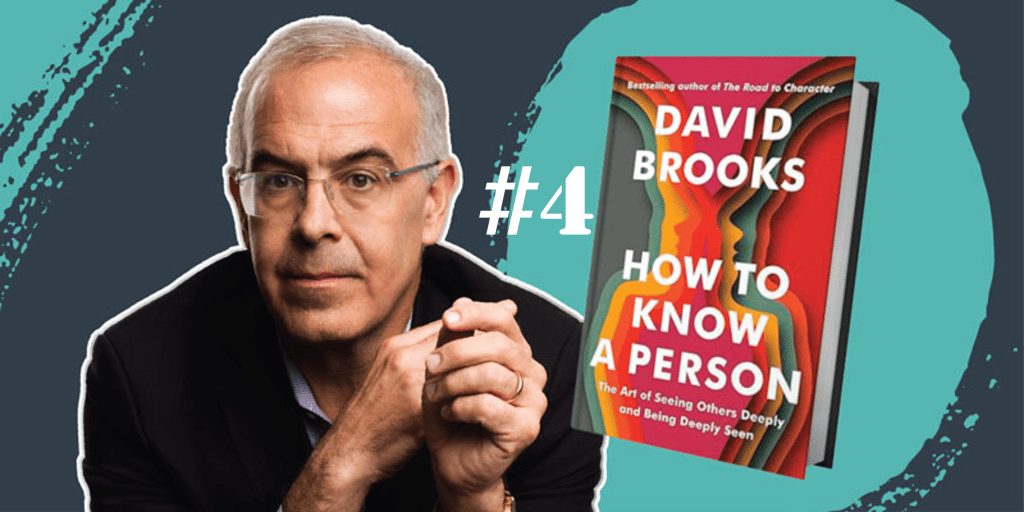

David Brooks, in How to Know a Person, uses this story as an example of the “naive realism” people often live in, assuming the way the world appears to them is “the objective view, and therefore everyone else must see the same reality…People in the grip of naive realism are so locked into their own perspective, they can’t appreciate that other people have very different perspectives.”

Granted, Pat didn’t say I was on the “wrong side,” but that’s how it felt. The idea of seeing people I rub elbows with daily lined up on opposite sides feels wrong to me. This constant “us” and “them” view diminishes the other person and never results in a coming together. Yet we all have these inborn proclivities that prevent us from perceiving each other accurately.

Other ‘diminisher tricks’ Brooks describes

- Egotism: Too self-centered and lacking in curiosity to try to see the other person. “Let me tell you my opinion. Let me entertain you with this story about me.”

- Anxiety: So much noise in our own heads we can’t pay attention to the other person. They may be riddled with fears about what to say next, whether the other person likes them, or whether they sound clever.

- Lesser-minds: We know what we think as well as what we say, but we only have access to what other people say, so we conclude we are much more complicated, more interesting, more high-minded than them.

- Objectivism: A detached stance that favors group data over the subtleties of individual people, such as their thoughts and emotions.

- Essentialism: A reliance on generalizations and stereotypes. This “stacks” people by learning one thing about them, then making a whole series of additional assumptions based on that one thing.

- Static Mindset: Not updating our models of who other people are as time passes. For instance, parents sometimes always see their children as the kids they once were.

I’m frighteningly aware that what I write about other people is less than who they REALLY are. “Seeing another person well is the hardest of all hard problems,” Brooks writes. “Each person is a fathomless mystery, and you have only an outside view of who they are.”

While that’s true, you gotta start somewhere. And that somewhere for me is writing about MY experiences, MY observations and MY feelings. That process naturally gets me thinking about the perspectives of others and makes me more curious about what makes them tick and how I can connect more genuinely. And then I begin to practice what I learn and write about what happens.

Writing is how I make sense of me and how I make sense of the world. That outside “naval-gazing” view is just a start.

Another reading of that old story

This time the story is told within the setting of Buddhism…

A young Buddhist on his journey home comes to the banks of a wide river. Staring hopelessly at the obstacle in front of him, he ponders for hours on how to cross such a wide barrier. Just as he’s about to give up, he sees a great teacher on the other side of the river. The young Buddhist yells over to the teacher, “Oh wise one, can you tell me how to get to the other side of this river?” The teacher ponders for a moment, looks up and down the river, and yells back, “My son, you are on the other side.”

On first reading, the stories sound a lot alike, but the Buddhist interpretation is different. Buddhism would say we should not focus on getting somewhere else but instead on seeing clearly for the first time where we already are. We are already there. There is nowhere to get to. We only have to be present where we already are.

‘Illuminator’ keys to being present

“Respect is a gift you offer with your eyes,” Brooks says, and shares some features of the illuminator’s gaze as antidote to the world’s ills…

- Tenderness: Holding a deep emotional concern about another human being that perceives what connects us, our similarities and sameness. An example is the way the artist Rembrandt rendered even the plainest people in such a remarkable way that he makes us see them anew.

- Receptivity: Overcoming self-preoccupation and insecurities to open ourself to the experience of another. Instead of projecting our own viewpoint, staying “patiently ready for what the other person is offering.”

- Active Curiosity: Having an explorer’s heart. Wonder what it would be like to believe and experience all sorts of things we didn’t believe and, in the process, experience what we can gain from other people.

- Affection: Considering the biblical idea of knowing as a whole body experience that goes beyond an intellectual exercise. Reason and emotion go hand-in-hand, not separately.

- Generosity: Seeing every person as the best of men or women. This is like the idea of the self-fulfilling prophecy presented in my college ed psych classes: However a teacher chooses to see a child is what that child will become. If you expect little, that’s what you get. Conversely, if you expect a lot, you get it.

- Holistic Attitude: Seeing the whole person. Doctors sometimes mis-see patients as merely bodies, while employers may mis-see employees if they look only at productivity. No one is all bad. No one is all good. We are all a mass of contradictions.

Morality is mostly about how we pay attention to others. The essential immoral act is the inability to see other people fully. The essential moral act is directing just and loving attention on another.

Will that attention–that experience of being seen–also open that person up to seeing the one who has seen them? Will the two on opposite sides of the river eventually find the bridge that proves there is more that joins them than divides them?

In these divisive times, that’s what I want to find out.

Look out, Lazy River, I’m comin’ for you.

You might also enjoy…

- Twisted Pool Talk #1, Babs’ Cataract Adventures: A Cautionary TikTok Tale

- Twisted Pool Talk #2, The Dangers of Spreading Weather Conspiracies

- Twisted Pool Talk #3, Navigating Political Conversations with a Talkaholic: Barbie Tales

- Twisted Pool Talk #4, The Misadventures of a Lost Stanley Drink Cup

- Exploring David Brooks ‘How to Know a Person’

- A Meaningful Encounter: Connecting Over Culture & History at Clinic Check-in

Use the comments to share…

- How you’ve experienced either diminishment or illumination from another.

- What “diminisher” traits are you guilty of?

- What “illuminator” traits do you struggle with?

Leave a comment