Post-election 2024 I treated myself to a subscription to both the New York Times and The Atlantic, where I’ve enjoyed David Brooks’ writing on politics and culture. Particularly, I was absorbed by “Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid.” (Sign up for a free 30-day trial if not a subscriber.) That article encouraged me to try Brooks’ latest book, How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen, published last year.

Brooks has been a New York Times columnist since 2003 and regularly contributes to PBS Newshour as well as The Atlantic. Though regarded as a moderate conservative in years past, he now describes himself as “on the rightward edge of the leftward tendency.”

This is not a book review per se, though I thoroughly enjoyed the book and have already started reading it a second time. I feel sure I’ll continue absorbing its contents, and my thoughts on its analyses and suggestions will likely reappear in future posts.

I’m not typically a reader of self-help books, but I decided to read this one to learn more about how other people think and it has delivered on that. But it also has helped me look at my own self with greater understanding, as an underpinning to connecting with other people in a more authentic way.

A family of defense architectures

Brooks outlines the common “architectures of defense” people carry throughout their lives as a means of protection. Reading through these felt like reading a map of my own key relationships and of myself:

Avoidance

This defense has its roots in fear, yet the person who carries it may appear to be the strong one who others turn to for support. Often these people didn’t have close relationships as children and so have lower expectations of future relationships. Emotions have hurt these people, so they try to minimize emotions in their lives. They often overintellectualize life and retreat to work. They may always be on the move and are sometimes relentlessly positive to hide their vulnerability.

My father largely operated within this architecture:

- We moved a lot because dad changed jobs or was transferred. We lived in seven different cities or states in eight years. I attended five different schools and had to build a new set of friends each time, which became increasingly harder as I got older.

- Wherever he relocated us–Pennsylvania, New York, back to Pennsylvania, on to Indiana–Dad always retreated into his work. My most potent memory of him is he was absent a lot. Nothing was more important than his job.

- Then, when he was fired from a job for refusing to falsify financial statements, he was admirably stoic, stuffing the anger he surely must have felt and working even longer hours at his next post.

My husband’s avoidance looks quite different from my father’s:

- He remembers feeling a great fear of nuclear war while going to school in the 1960s. Then at age 8, he contracted rheumatic fever and spent a year bedridden, unable to attend school.

- He stoically survived 10 years of an unsatisfying marriage before meeting me. Though always loving and accepting of my emotion, in the early years of our marriage he had difficulty getting in touch with his own. He is still “the strong one” to me and particularly to his daughter, and I know he often feels the burden of it.

Deprivation

If you’re raised around people who are so self-centered they ignore your needs, you naturally learn your needs won’t be met, and you may eventually think you’re not worthy. Children raised in such an environment often believe there’s some flaw deep within themselves that would cause others to run away from them. When treated badly, they blame themselves.

My mother largely operated within this architecture. Her family was economically deprived as well as emotionally deficient. You can read more about her childhood of deprivation in my earlier post, Miss Wear-Ever: A Journey of Self-Confidence.

My mother’s defense architecture of deprivation caused her to always want things for her children that she didn’t have growing up. Often this was good: She was adamant all three of her children would graduate college, and she worked part-time to supplement our family’s income and make it happen. But sometimes she was blind to the fact that I wanted something different from what she wanted for me. I touched on this in the linked post above and plan to write more about a particular instance not covered there.

Overreactivity

Threatened and abused children grow up in a dangerous world and often have a hyperactive threat-detection system wired deeply within themselves. Thus, they may see menace where none exists. They overreact to situations and fail to understand why.

My stepdaughter suffers from overreactivity, largely because of issues with her biological mother. As a consequence, she started abusing alcohol and prescription drugs during her high school years. She’s been sober going on 13 years, but still struggles with overreactivity. She expects people not to “show up” for her, even though many–including her dad and I, as well as AA friends–do, over and over again.

Overreactivity has also been a defense architecture I’ve used throughout my life. I experienced an event of physical abuse when I was 6 and ongoing emotional withholding that, in retrospect, I believe pushed me into evangelical Christianity during my high school and college years. It was a barrier I erected to protect myself from hurt. When I no longer lived in my parents’ home, I lost interest in it.

Passive Aggression

This is an indirect expression of anger and a way to sidestep communication by a person who fears conflict and has trouble dealing with negative emotions. This person may have grown up in a home where anger was terrifying, where emotions were not addressed, or where love was conditional.

I have unknowingly used this defense architecture as well, though it’s not something I think characterizes me now. Growing up, my father’s anger WAS terrifying, and he was quick to denigrate any expression of emotion on my part or my mother’s. Often tears would come to me unbidden–I’m sure out of frustration–which only escalated his anger.

Too much information or not enough?

I’m amazed how, after thinking about the ideas presented in this book, different people can be pushed into the same defensive architecture by highly different circumstances. I also find it interesting how we cross over into different categories, depending on circumstances and aging.

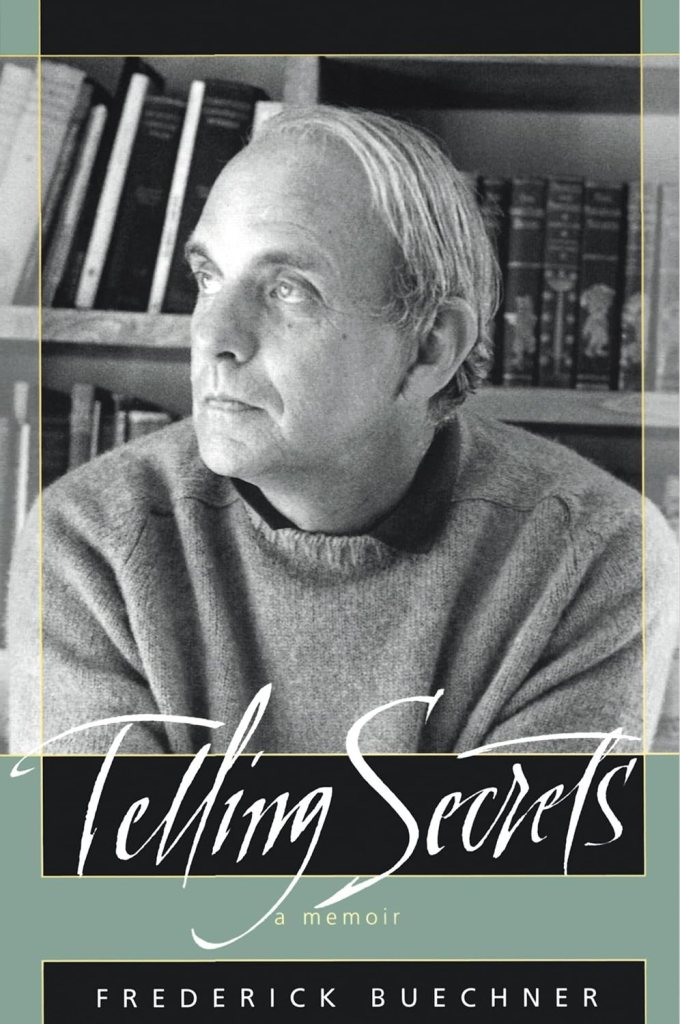

You may be thinking by now, however, that it’s TMI–too much information. Consider then this passage Brooks quotes from Frederick Buechner’s Telling Secrets:

It is important to tell at least from time to time the secret of who we truly and fully are…because otherwise we run the risk of losing track of who we truly and fully are and little by little come to accept instead the highly edited version which we put forth in hope that the world will find it more acceptable than the real thing. It is important to tell our secrets too because it makes it easier…for other people to tell us a secret or two of their own.

Brooks says the repeated excavation gives us “mental flexibility,” that is, the ability to hold multiple perspectives on a single event, “To find other ways to see what happened. To put the tragedy in the context of a larger story.” The Swiss Psychiatrist Carl Jung called it “holding the tension of the opposites.”

I’m relying at first on examples from my own life as a way into a greater story I hope to write with others. I want to do this because, as Brooks says…

Stories capture the unique presence of a person’s character and how he or she changes over time. Stories capture how a thousand little influences come together to shape a life, how people struggle and strive, how their lives are knocked about by lucky and unlucky breaks…You get to experience their experience..

And then he adds…

By sharing their stories and reinterpreting what they mean, people create new mental models they can use to construct a new reality and a new future. They are able to stand in the rubble of the life they thought they would live and construct from those stones a radically different life.

This is where I want my election grief to take me: to a new experience of people who think differently than me. And, possibly then, to midwife them to a new experience of themselves.

PLEASE NOTE: This post contains affiliate links.

Use the comments to share…

- What defense architecture you think mostly describes you and why

- How learning about defense architectures changed how you view your relationships

- Your experience of telling a personal secret

- A secret you’ve never told before

Leave a comment